*Published with the generous permission of Teri Kanefield. Read all of her writing here.

Teri Kanefield

Welcome to Criminal Law and Criminal Procedure 101. I’ll cover it all, so take out your notebooks. Warning: This stuff is so interesting that when we get to the end of this series you may start asking how to apply to law school.

At the end there will be a test, so please pay attention.

Before we can get to criminal procedure, we have to talk about criminal law in general. You have to know what something is before you can discuss how to enforce it. So, let’s start with the basics:

What is a crime and how do we decide which behavior to criminalize?

A crime is behavior that is punishable as a public offense.

Not everything bad or immoral is a crime. Cheating in a poker game with a friend isn’t a crime. Lying to your spouse about where you were last night isn’t a crime. Conversely, not everything that has been criminalized is bad or immoral. For example, before the Civil War, helping an enslaved person escape was a crime.

Laws — including criminal statutes — reflect the values of the lawmakers. As the culture changes, and the attitudes of lawmakers change, laws change.

The Rule of Thumb

For example, there was a time when it was considered bad policy to punish domestic violence. This is illustrated by the 1868 case of State v. Rhodes.

The husband, A.B. Rhodes, was charged with battering his wife. The evidence presented at his trial showed that he struck her three times with a switch about the size of one of his fingers but not as large as his thumb. The size of the switch was important because under common law at the time, a man could legally beat his wife if the switch he used was no bigger than his thumb—the so-called rule of thumb.

Rhodes’ defense was that his wife had said something that enraged him. At the trial, he couldn’t remember what it was. Because he couldn’t remember what she had said, the trial court concluded that she had done nothing to deserve the beating. Nonetheless, the court found A.B. not guilty of battery because the switch he used was smaller than his thumb.

The case went on appeal to the North Carolina Supreme Court.

The North Carolina Supreme Court rejected the Rule of Thumb and held that a husband does not have the legal right to beat his wife. If A.B. had beaten someone other than his wife, he would be found guilty of battery. However, because the wife’s injuries were not severe, the court felt that finding A.B. guilty in this case would cause greater harm to society than whatever harm his wife sustained from his beating.

The court explained that, if the beating was not severe, interfering in marital disputes would cause more harm than good because a wife could—and should—forget “temporary pain,” but if she took her domestic quarrel public, the pain of public humiliation for the family would not be easily forgotten and would cause more long-term damage to the family. Moreover, the court reasoned, courts should not try to resolve domestic quarrels because there was no way to really know who was at fault. After all, “Who can tell what significance the trifling words may have had to the husband? Who can tell what happened an hour before, and every hour or a week?”

The court referred to the beating as “moderate correction” and said, “We will not interfere with or attempt to control [families] in favor of either husband or wife, unless in cases where permanent or malicious injury is inflicted or threatened, or the condition of the party is intolerable.”

The North Carolina Supreme Court’s attitude toward domestic violence in 1868 reflected the general attitude of courts and law enforcement until relatively recently. Until late in the 20th century, police and law enforcement generally closed their eyes to domestic violence. Eventually that changed under pressure from women’s activists.

Types of Crimes

There are four categories of crimes: (1) Violent crimes, such as murder and battery; 2) Property crimes, such as burglary and vandalism, 3) White collar crimes, such as financial fraud, tax evasion, and embezzlement, and (4) victimless crimes where nobody is injured (drug possession is considered a victimless crime.)

When Rape Was A Property Crime

Throughout most of our history, rape was a property crime, which makes sense if a woman is considered property. An unmarried girl was her father’s property. A married woman was her husband’s property. If a virgin was raped, the property damage was to her father. If she was married, the damage was to her husband.

If she wasn’t a virgin and wasn’t married, there was no crime (because the property was already damaged). A man couldn’t rape his wife (his own property) and rape of enslaved women wasn’t a crime. Attempted rape wasn’t a crime because there was no property damage.

Rape laws were generally intended to protect (white) men from false accusations. They were not intended to protect a woman from attack. (A woman was expected to guard the goods.) If she was raped, courts wanted to know what she had done to prevent, or invite, the attack. A woman’s word was generally not sufficient evidence to prove the crime of rape — unless a white woman accused a Black man. Then, she was taken at her word.

Until the second part of the 20th century, rape was difficult to prosecute. Then, in the 1970s and 1980s, under pressure from women activists, that began to change. (For more on that, see Rape is a Means of Asserting Patriarchal Power.)

Financial Crimes

Until relatively recently, white-collar crimes often went undetected because there were so few regulations or means of investigating such crimes. It wasn’t until the 1970 Bank Secrecy Act that law enforcement was given the ability to detect money laundering and bank fraud.

During the decades since, as the public has come to recognize the seriousness of financial crimes, other laws have been passed making it easier for law enforcement to gather evidence of financial crimes.

To Criminalize or Not To Criminalize (that is the question)

A person can be held responsible in civil court for damage they cause when they are negligent, careless, or cause deliberate harm. With rare exceptions (such as punitive damages) a person is not punished in civil court. Instead, they are ordered to pay for the damage they cause or cease harmful behavior.

In a criminal case, the remedy is punishment.

In a civil case, one citizen brings an action against another (or a person sues the government). In a criminal case, the government brings the action against an individual.

The differences are profound. Punishment is the deliberate infliction of pain. In a criminal proceeding, the government — with its vast power — is seeking to deliberately inflict pain on an individual. This, by the way, is why I believe issues of criminal law and procedure are the most important legal issues.

Deciding which behavior should be criminalized is not as easy as you might think.

A few decades ago, California was considering passing a law making it a crime for a parent to engage in domestic violence in the presence of a child. The punishments included imprisonment. One of my former law professors recommended that an advocacy group hire me to write an argument against passing the law.

I did the research and learned that “engaging in domestic violence” included getting beaten up by a domestic partner and that most people who were beaten up by domestic partners were women trapped in bad relationships. It was almost always the man who did the beating.

I’m sure that the legislator who proposed this particular law meant well. She wanted to deter bad behavior and protect children. Indeed, beating up your wife in front of the kids is certainly terrible behavior that society has an interest in deterring, but it seemed to me that criminalizing and incarcerating the person who was getting beaten was not a sensible remedy.

I wrote up my research and argued that such a law would criminalize the victims of domestic violence instead of offering intervention and help. The organization offered my arguments to the state legislators and emphasized a phrase I used, “The law will criminalize victims.” The law was not passed.

If you don’t like the criminal laws in your jurisdiction, pay attention to local elections and elect lawmakers who share your values about what should be criminalized and where law enforcement should focus its attention.

Some people think the way to improve the country is to criminalize more bad behaviors. They think if we punish more bad people, we will solve our woes. Others think that overcriminalization is a problem.

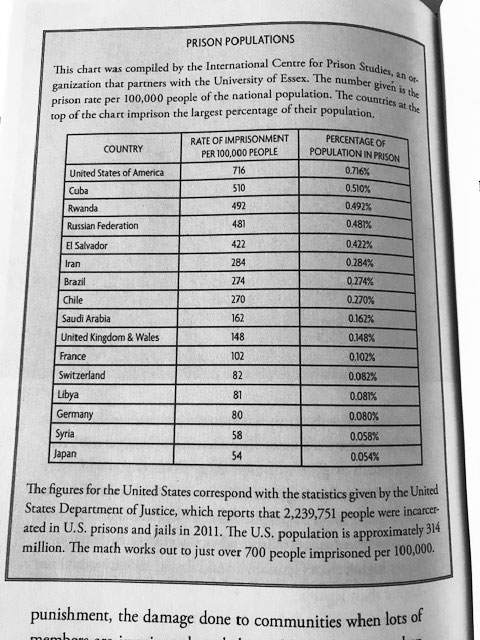

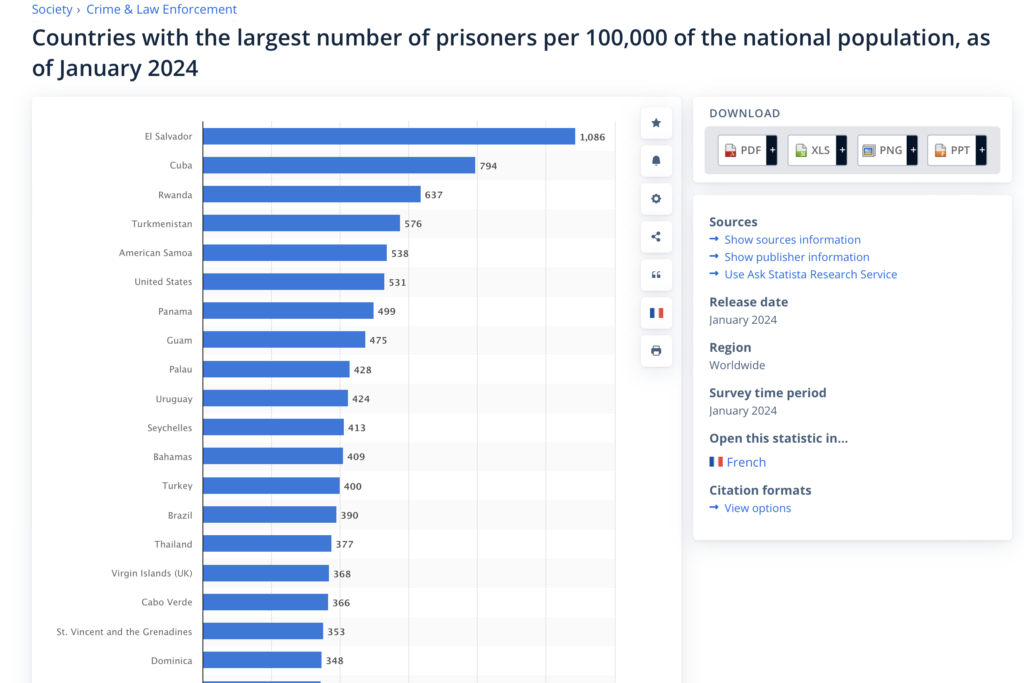

In 2014, the United States led the world in rates of imprisonment:

Here is today’s test question. It is multiple choice. Here is a question I often get:“A person in Texas was jailed for something trivial. A person in California did something far worse and is out on bail. How can that be?

How would you respond?

And now, a story.

My stepson is a law-abiding man in his thirties, but he was once a cheeky kid who liked messing around with rules. While I was studying for the bar exam, he amused himself by reading my flash cards. As a result, he understood things like the requirement that people have fair notice of what behavior is punishable.

One night at dinner when he was about twelve he asked me, “Can I get in trouble for doing something if it isn’t listed in the school manual?”

I understood why he was asking, so I said, “Yes, you can get in trouble. Some rules are so general that they apply to lots of things. For example, you’re not allowed to do something risky that will endanger yourself or anyone else.”

“But what if it’s something that isn’t dangerous?” he asked.

“Like what?”

“Well, for example, getting up on the school roof.”

My husband looked him in the eye and said sternly, “Don’t do it.”

The next day I received a phone call from the middle school principal. You guessed it. My stepson and a friend had climbed on the roof of the two-story school building. After being brought to the principal’s office, my stepson informed the principal he had a defense: There was nothing in the list of school rules against climbing onto the school roof, so he could not be punished for it. The principal was not persuaded. My stepson was suspended from school.

Later my stepson was pleased to report that the middle school manual now contains a rule against climbing onto the school roof.

Why I Shut Down My Comment Section

This is my personal website so I need to moderate the comments, and the task was becoming too time-consuming. This way I can publish my blog on Saturday and take off Saturday evening and Sunday. I have deadlines with my next book and limited time.

But I often get ideas for blog posts from the comments. So here’s a contact button for questions and comments. I will probably not answer. Instead, I may select a few to answer here.